This isn’t going to end like this.

Two years ago, this was Débora’s thought when she took the first survey through Unbound’s Goal Orientation powered by Poverty Stoplight and gained a better understanding of her situation.

At 40 years old, Débora had lived her entire life sharing a home with her parents and great-grandmother. She single-handedly raised her son, embroidering and teaching at an elementary school to earn a living in her rural Guatemalan community. She had never felt the peace of solitude and the independence that could grow from simply having the option of privacy in her living space.

The results of the Poverty Stoplight survey indicated several areas in her life that she needed to improve upon if she wanted to one day be free from poverty. One of those areas was “Housing and Infrastructure.”

“I said to myself, ‘If this [survey] gives me the option to be independent, I have to achieve it,’” Débora said. “[My life] isn’t going to end like this — I must have goals and plans. So, I wrote on the [goal] sheet that, one day, I would have a space to be, a space where I could be alone and independent.”

Débora had longed for a home for her and her now 17-year-old sponsored son, Hamilton, but the financial obstacles she had to overcome to make her dream a reality seemed insurmountable. She needed something to motivate her, to help her visualize a clear path forward. The goals she created with her first Poverty Stoplight survey helped her do that.

“Many people say it can’t be done,” Débora said. “Now that I see it, you can do [hard] things when you want to, but it also requires willpower.

And, when you say, ‘Yes, I can,’ you achieve it.”

September 04, 2025 | Poverty Stoplight

Peace in a tiny home

A mother and son build the home of their dreams using Poverty Stoplight as a guide

By Kati Burns Mallows

I said to myself, ‘If this [survey] gives me the option to be independent, I have to achieve it. [My life] isn’t going to end like this — I must have goals and plans.’ So, I wrote on the [goal] sheet that, one day, I would have a space to be, a space where I could be alone and independent.

— Débora, Mother of Unbound sponsored youth Hamilton in Guatemala

The 'tiny house' filled with dreams

The average size of a single-family home in the U.S. today is just over 2,000 square feet. In a country where bigger is often equated with better, the opportunity to own space is a luxury that many take for granted.

But the sense of comfort and privacy that comes with having personal space is universal — it’s freedom, cleverly disguised as square footage.

Débora’s freedom came in the form of 387 square feet of cinderblock, plaster and cement.

Obtaining their own living space was one of the first goals she and Hamilton set together with the help of Poverty Stoplight.

Using some of the funds saved from Hamilton’s cash transfer sponsorship benefit, income generated from selling chickens and a small loan, Débora built the two-room house on land inherited from her parents, next door to their family home. One room of the house is Hamilton’s bedroom, while the second doubles as a multipurpose room and Débora’s bedroom. The house still lacks a kitchen and running water, but these are future goals Débora is already working toward.

It took her just over a year from the time she took the Poverty Stoplight assessment to complete her home.

“From [Poverty Stoplight], what surprised me was to see where I am now,” said Débora about taking the follow-up survey later. “We [people in poverty] have to think about getting out of the daily routine so we can make a little more effort to achieve what we want.”

Débora and her son, Hamilton, 17, sit on the porch of their new 387-square-foot home in Guatemala they built as part of their first Poverty Stoplight goals.

A high-achieving student, Hamilton studies accounting in high school and plans to one day be an entrepreneur. The new home has given Hamilton a dedicated space to study so that he can focus on his educational goals.

Understanding poverty to eliminate it

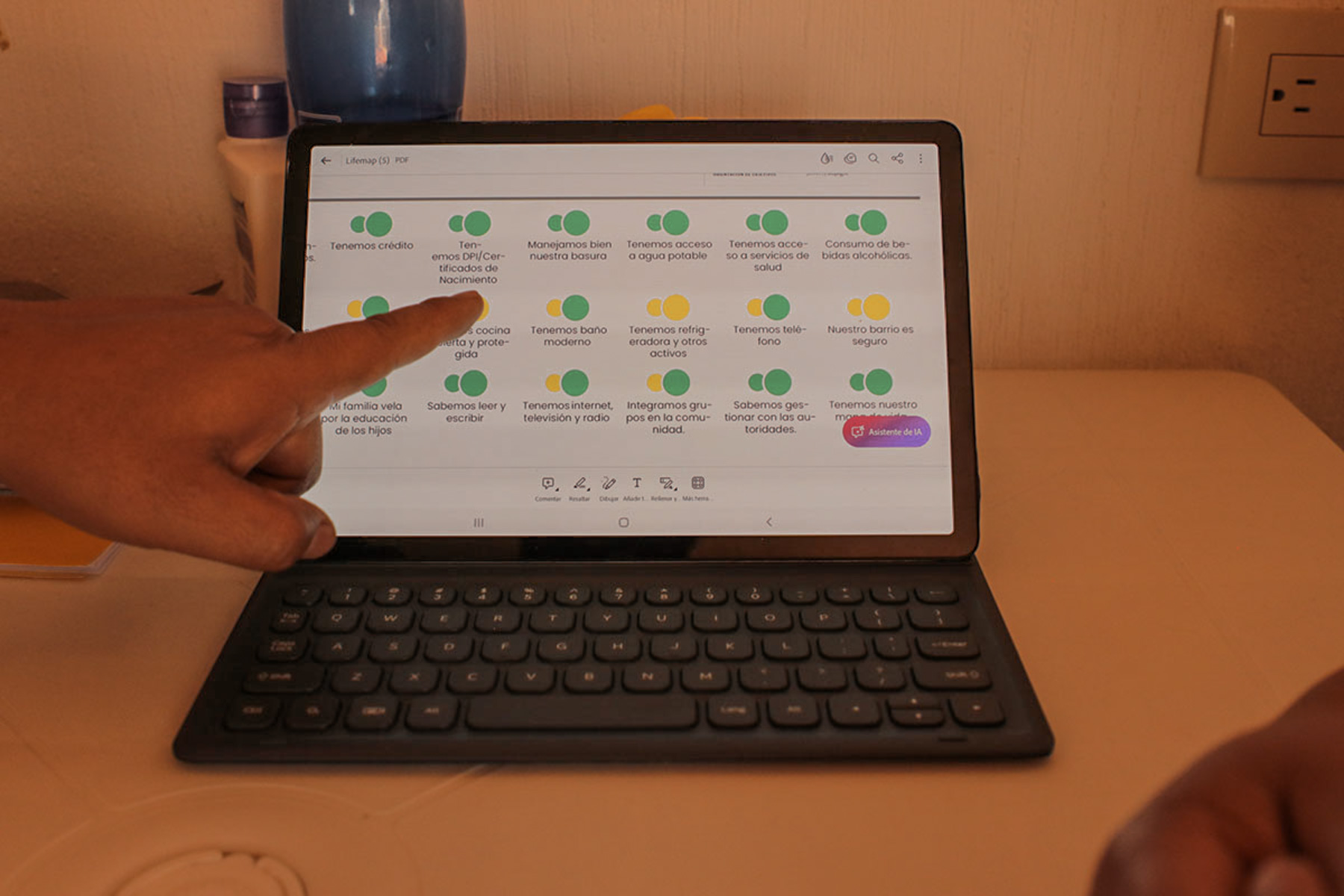

Poverty Stoplight is a mobile technology and social innovation platform developed by Fundación Paraguaya and adapted by Unbound to fit families’ needs. The tool allows families to self-assess and reflect on their poverty situation. They identify the roots of their poverty by marking indicators in red (extreme poverty), yellow (poverty) or green (no poverty), and it’s this process that generates a plan, referred to as the “life map.” Since its implementation in 2020, over 250,000 households in Unbound’s programs around the world have used Poverty Stoplight to set personal goals to help them eliminate poverty from their lives.

Director of Program Evaluation for Unbound’s Guatemala office, Andrés González Peneleu, guided Débora through the Poverty Stoplight assessment. Débora took extensive training offered by local staff to help families achieve their poverty-elimination goals.

“We teach them how to set SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-Bound),” Peneleu said. “They have a set timeframe for the goals they want to work on and how they will work on them. After six months, we measure their progress, and at a year, they take the survey again.”

In Débora’s Unbound community, most families indicate having “extreme poverty” (red) in the areas of “Housing and Infrastructure,” “Income and Employment” and “Health and Environment.” According to Peneleu, since Unbound’s Guatemala program began using Poverty Stoplight, they’ve seen families overall steadily begin to improve their poverty indicators, from 57% of indicators in the green in 2023 to 64% in the green by the end of 2024.

In the beginning, areas in “red” for Débora were mostly housing and environment-related — no home of her own, and no running water or electricity. Today, only water remains in “red,” while her home has moved to “yellow.”

Débora is already working on her next goals. She’s completed paperwork with the local city government to obtain running water and a sink for her small home (the thing that will help move her home into “green,” the no poverty status), and she hopes to be able to start building a second level to her home in another year.

The director of program evaluation for Unbound’s Guatemala office, Andrés González Peneleu, pays a home visit to Débora to discuss progress with her goals.

A look at the mobile technology platform Poverty Stoplight and the indicators Débora has turned to “green” (no poverty).

Peneleu believes that each community where Unbound operates has its own reality in terms of poverty and so does each family. Besides the tangible benefits families can glean from using Poverty Stoplight, it can offer intangible benefits as well, as staff have discovered.

“Subjective indicators like emotional issues and [low] self-esteem are also a part of multidimensional poverty and knowing about them can also help us escape poverty,” Peneleu explained. “For example, if you say to someone, ‘What do you prefer — having running water or being at peace with yourself?’ Most families tell us, ‘I prefer being at peace because I can walk to get water.’”

For Débora as a single mother, it was gaining self-esteem that she said changed her life. Attending workshops and trainings on entrepreneurship and leadership development offered by Unbound and being elected by her peers to lead her Unbound mothers group helped her realize her true value.

It ultimately gave her the courage to fight for the things that could introduce peace to her daily reality, like the tiny home she now calls her own.

“Many people tell me how beautiful it is where I live, that it is a very peaceful place,” she said with a smile. “Look, by the grace and mercy of God, where I am — this house was my goal, and today, I enjoy it.”

Débora and Hamilton walk their property at their homestead in Guatemala. Business development strategies they learned through their Unbound small group have helped them create a successful business raising, butchering and selling chickens, the earnings of which helped them fund much of the construction of their new home.

Unbound Regional Reporter Oscar Tuch contributed information and photos for this story.